A new book project called Your Land researches a period of land activism after the Civil Rights Movement that linked the US South and the Global South.

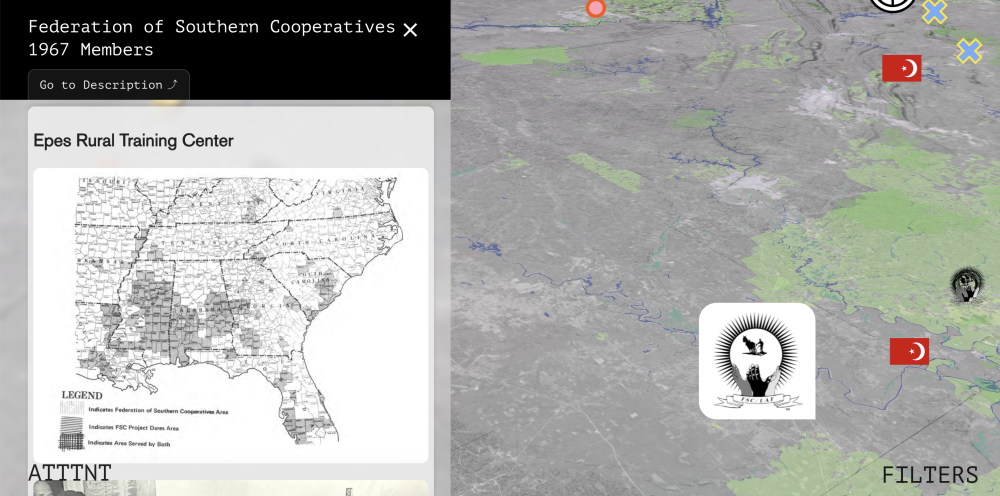

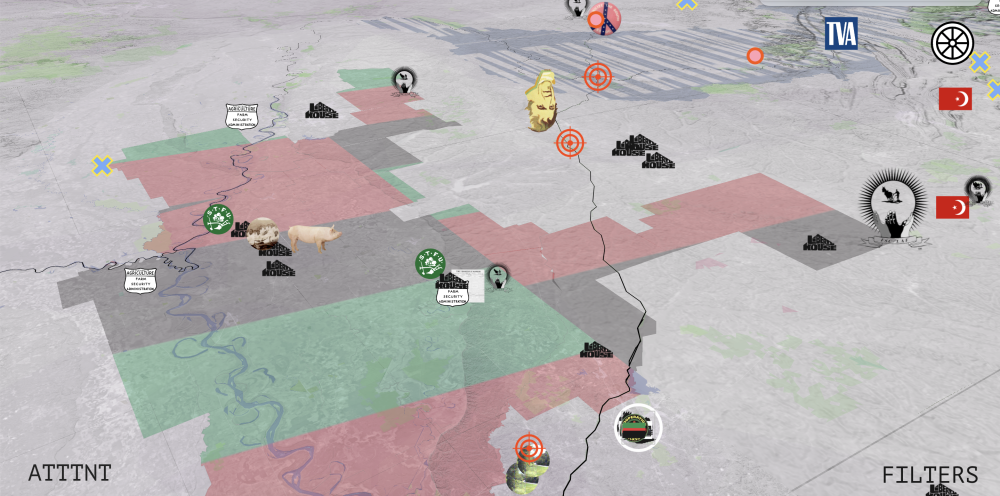

Black land ownership in the US dropped from 15 million acres in 1910 to 3 million acres in 1970. In the 1960s, among the many activists who traveled to the South to fight for civil rights, some remained to expose forms of land theft and support the Black economy with cooperative organizations. A constant undertow of white violence, abetted by government agencies, prevented further retention or restoration of land, but the detailed work, often in collaboration with HBCUs, identified land assets and developed land-holding organs and Black institutions to manage those resources.

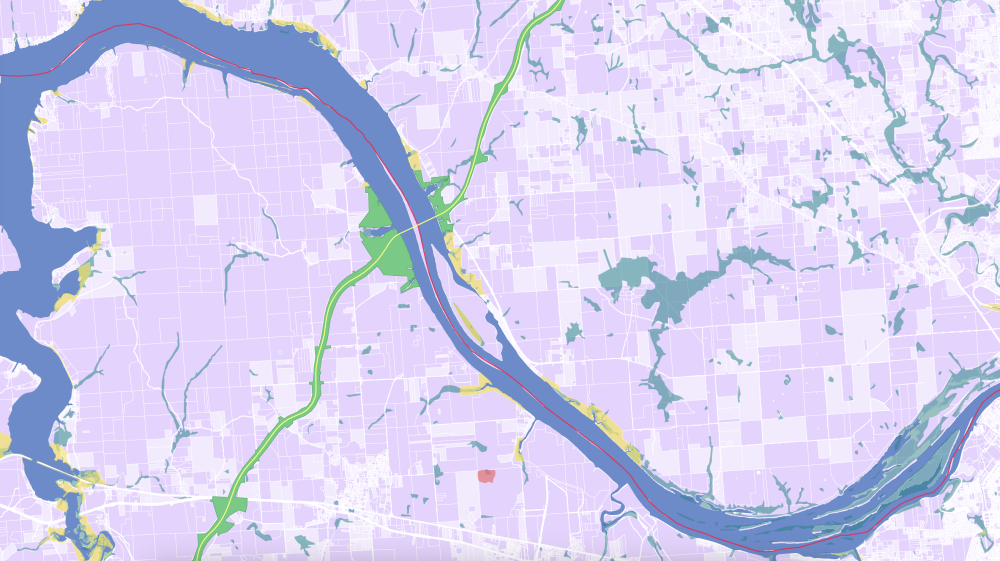

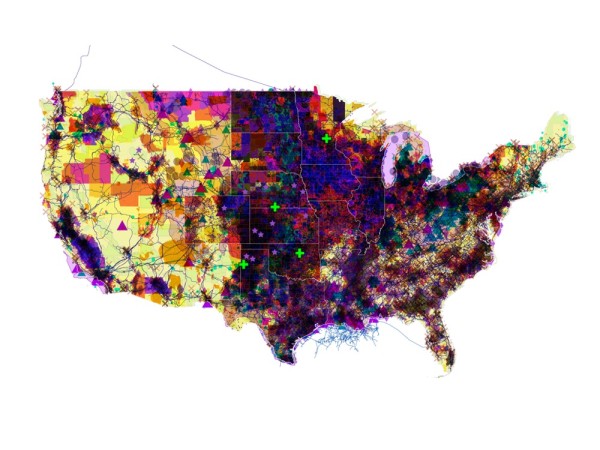

When reconstructed, the work maps a scar across the US that does not try to cover over its ugliness and pain. Both recalling and foretelling, it tallies crimes beyond those of slavery and identifies patterns of harm that are root causes of future climate dangers. Tracking the transition from Dixiecrats to the Southern Republicans of Nixon and Reagan, this history also recalls recurring strategies that Trump has redeployed to craft the current polarized entrenchment.

Still, Returning to areas weighted with multiple traditions, a reconstruction of these efforts begins to materialize, within the same Black Belt crescent, a special infrastructure possessing the superabundant values of land, community, and education—an infrastructure as worthy of public investment as infrastructures of concrete and conduit. And it renews planetary political solidarities from the 1960s and 70s with the capacity to shape to reparations for the past and preparations for the future.

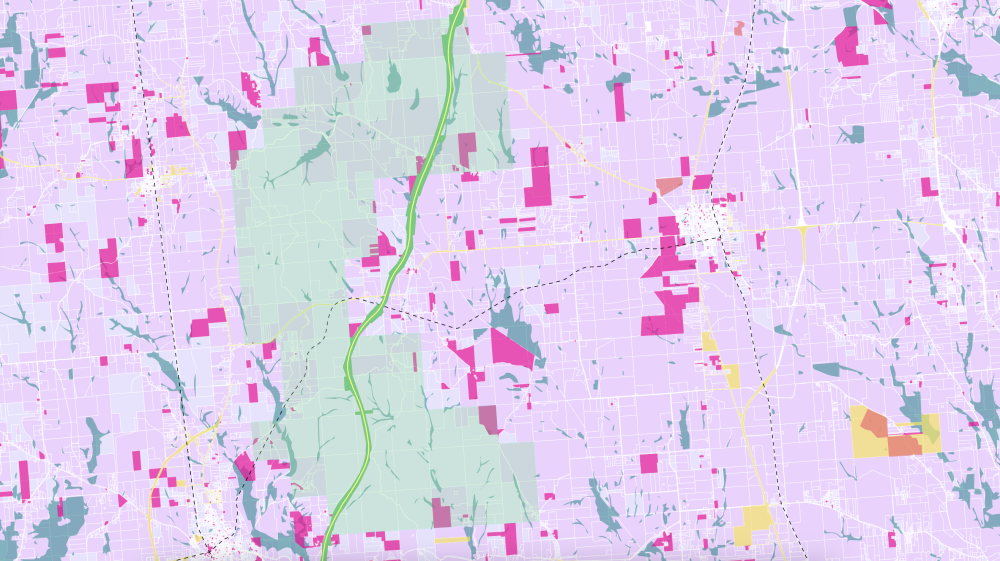

The project uses mapping and storytelling to make palpable this existing infrastructure—a network of HBCUs, Black institutions, and cooperative communities—as a framework to receive and manage multiple approaches to reparations. It is already positioned to redouble assets and address an incalculable debt with incalculable values related to land, community, and education. Given its proximity to large federal land holdings, the project also identifies some immediate federal and private resources to thicken and enrich it.

These Black geographies probably don’t exist on a white mental map of the US South that might be decorated with obscene cartoons of manifest destiny, confederate glory, and stolen Indigenous imagery. But, strangely, a thin strip of public land often scripted with white supremacist narratives coincides with the Black Belt crescent. The Appalachian Trail (AT), the water route of the Trail of Tears (TT), and the Natchez Trace Parkway (NT) form a 3000 mile long ribbon of land that sits silent and inert as it passes through formations about which it is largely ignorant and about which it might now have some reckoning.

This is ATTTNT—at once code for whiteness itself as well as code for a claim to public lands as reparations.

Morgan State/Jackson State Partners: Samia Kirchner and Thomas Kersen

Website team: Keller Easterling, Alvin Ashiatey, Bianca Ibarlucea, Nicholas Arvanitis, Hima Goburru, Elis Huang, and Rebecca Mqamelo